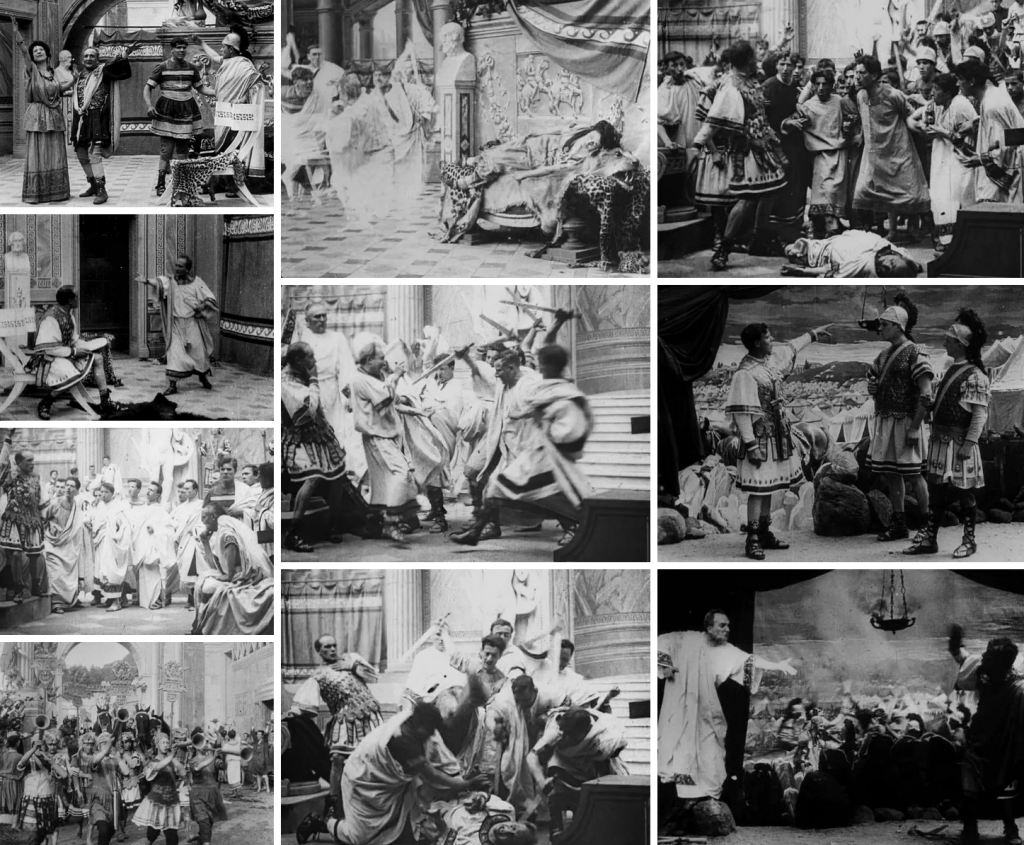

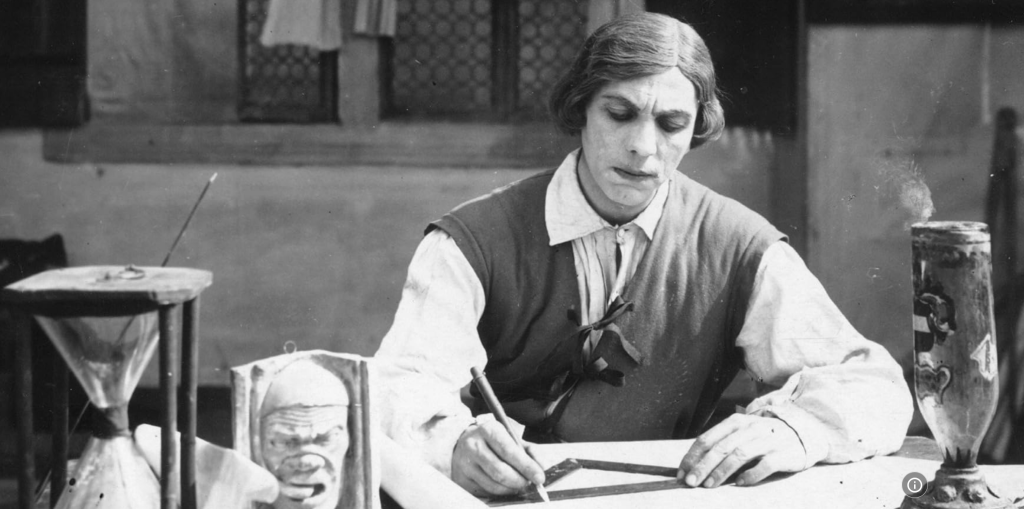

Today we’re talking about Giovanni Pastrone’s Giulio Cesare (1909). Although historically inaccurate and riddled with several issues, this film is fascinating because it represents one of Pastrone’s earliest attempts at staging a large-scale production with numerous extras. Interestingly, Pastrone himself also plays Julius Caesar in the film! Let’s start with the plot:

Caesar (Giovanni Pastrone) returns victorious from Gaul. Brutus (Luigi Mele) realizes he aims at tyranny and organizes strong opposition against him. Despite this, Mark Antony manages to secure Caesar’s triumph and coronation with the Senate’s support. Calpurnia dreams of Caesar’s death, warns him, but cannot prevent him from meeting his fate. Caesar is assassinated, and Mark Antony stirs the people against the conspirators, forcing them to flee. Justice is finally achieved after the Battle of Philippi, where Brutus dies of a heart attack after seeing Caesar’s ghost accusing him.

Of course, the actual story was quite different, since the film is more closely inspired by Shakespeare’s play than by history. In reality, after his proconsulship in Gaul, Caesar in 49 BC was supposed to return to Rome to stand for consulship, but feared that Pompey and the Senate were plotting against him. He asked to be allowed to run for office while remaining outside Rome, but his request was denied. He then crossed the Rubicon (alea iacta est!) and ignited a civil war between the Caesarians and Pompeians, which ended with Caesar’s victory. So, unlike the film’s abrupt transition, his return to Rome and his triumph was not immediate at all. It was only in 44 BC, after years of accumulating power, that Brutus, Cassius, and other senators organized the famous conspiracy.

One particularly interesting detail is the dream of Calpurnia, which the film includes. This comes straight from Suetonius, who mentions several ominous signs before Caesar’s assassination:

On the night before his death, Caesar dreamed he was flying above the clouds and shaking hands with Jupiter; meanwhile, Calpurnia dreamed the roof of their house collapsed, and her husband was killed in her arms. Then suddenly, the doors of their bedroom flew open on their own.

In the film, Calpurnia’s dream is treated purely as a premonition of the murder, which indeed takes place shortly afterward. Historically, however, Caesar was killed on the Ides of March, 44 BC, and the hunt for the conspirators culminated with the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, where Brutus, defeated, committed suicide.

Pastrone’s Julius Caesar also reveals several stylistic elements worth noting: his interest in perspective is evident from the very first scene, when Caesar returns from Gaul—appearing first in the background of the shot before stepping into the room. Also striking is the experimentation with crowd scenes, both in the triumph and in the Senate sequences. Pastrone already demonstrates a strong command of staging large groups, keeping even the most chaotic moments clear and well-organized. From a scenic point of view, however, there remains the common early-cinema tendency to blend pseudo-Greco-Roman elements with exotic or oriental touches.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment