Batalion could be likened to a song by Bob Dylan, a drama devoted to society’s outcasts, a series of interwoven stories of suffering that inevitably lead to tragedy, yet without losing their humor and humanity. The film is based on a 1922 novel by Josef Hais Týnecký, part of his socially conscious works. Compared to what we’ve seen so far in Czech silent cinema, this film is entirely different: dark, sorrowful, yet strikingly realistic, set in one of the most iconic spaces for Czechs…the tavern. Here, amidst every kind of alcohol, men’s stories intersect, offering fleeting moments of understanding and acceptance.

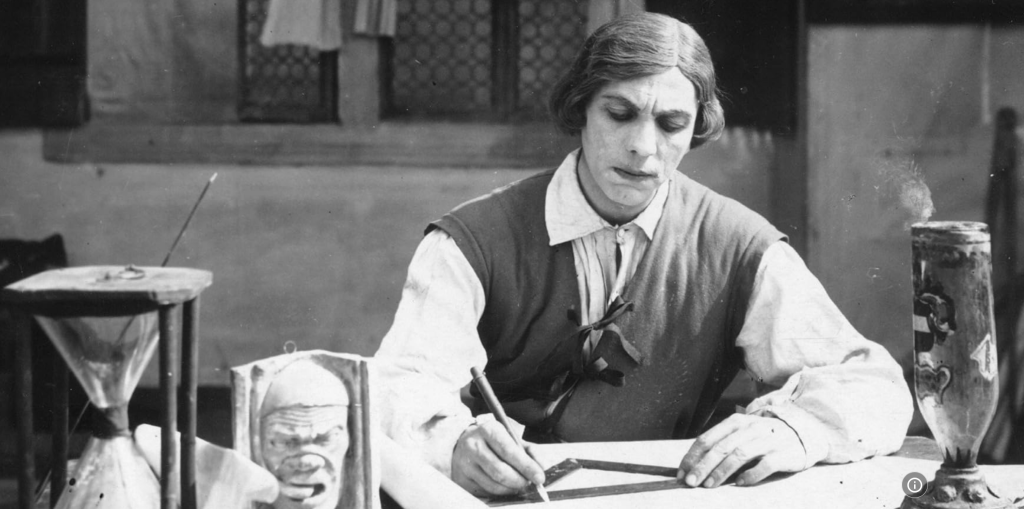

The lawyer Uher (Karel Hašler) discovers his wife’s infidelity and attempts to kill her but cannot summon the courage. He abandons his home and work and seeks refuge in the Batalion Tavern, a haven for the downtrodden whose lives gradually entwine with his. Among them are the failed actor Mušek (Eugen Wiesner), the prostitute Tonka (Jindra Hermanová), the bricklayer Rokos (Vladimír Smíchovský), the ex-soldier Vondra (Karel Noll), the chicken thief Bylina (Karel Švarc), and poor Eda (Eman Fiala). Tonka suggests marriage to Eda so she cannot be deported if arrested; he accepts despite being gravely ill, and they celebrate at the Batalion. Upon leaving, he is killed in a police raid targeting a thief. Uher decides to defend the tavern’s outcasts in court but loses. Nevertheless, he becomes a local hero at the Batalion, spending ever more time there and unraveling his own life. A glimmer of hope appears when Olga (Nelly Kovalevská), daughter of the court president, offers him a job as an organist. Believing she loves him, Uher accepts, only to discover she is engaged to someone else. He returns to the Batalion and, after a night of delirium, dies on his bed, forgiving his wife. In the final scene, the tavern’s patrons mourn him at his funeral, demonstrating that friendships among society’s outcasts can be deeper and more enduring than those in polite society.

The cinematography is meticulously crafted. I was particularly struck by the opening scene, which plunges the viewer directly into Uher’s imagination: he believes he is about to kill his wife and her lover, but in reality, he abandons his home for the Batalion. This interplay between imagined and actual events recurs throughout the film, reaching its peak in Uher’s final delirium, where superimpositions and camera movement allow the audience to experience the despair of a man who has lost all certainty and trust.

The characters populating the Batalion are diverse and vividly realized, bringing warmth and human connection to a story otherwise dominated by pain and suffering. Even when Uher finds a job that promises hope, the viewer remains invested in his return to the tavern—the only place where he feels truly accepted. The film’s darkness is conveyed through low-key lighting and shadow-heavy cinematography, enhancing its realism and emotional intensity.

Stories of this sensitivity feel uniquely Czech. In my years of studying silent cinema, I have never encountered a work quite like Batalion. I highly recommend it to anyone with the opportunity to watch it.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment