Today’s film takes inspiration from one of Tolstoy’s lesser-known novels, The Kreutzer Sonata. The story is fairly traditional, centering on a man, Pozdnyšev, and his intense jealousy toward his wife, with whom he has a complicated relationship. From what I have seen of the plot, this adaptation seems reasonably faithful to the original work, though I reserve judgment until I can read the novel myself.

A group of men are traveling on a train and discussing love. One man recounts the story of Mr. Pozdnyšev (Jan W. Speerger), who, in a fit of jealousy, killed his wife Nataša (Eva Byronová). Coincidentally, Pozdnyšev himself is present. Everyone else leaves, frightened, except the man who began the story, who listens to Pozdnyšev recount his life. As a young man, Pozdnyšev was romantic and trusting. When he met the beautiful Nataša, he immediately decided to marry her. After the wedding, the couple discovers they have little in common, and their love turns into mutual resentment, exacerbated by Pozdnyšev’s jealousy. When a doctor informs them after their third child that they cannot have more children, Nataša turns to a worldly life, spending lavishly on clothes and jewelry. At a social event, she meets the violinist Truchačevský (Miroslav Paul), who becomes a frequent visitor to her home and performs the sonata that gives the story its title. Pozdnyšev must leave on a business trip, relieved that the violinist is also away on tour. A few days later, he receives a letter from his wife stating that Truchačevský has not left and requested her to perform for him at a series of events—a proposal she had refused. Driven mad by jealousy, Pozdnyšev rushes home by train and, finding his wife and the violinist together at night, murders her, convinced of her infidelity.

A key element faithfully adapted from the book is the ambiguity of Nataša’s betrayal. While Pozdnyšev sees images of the two kissing, it is unclear whether they are real or a product of his imagination. Even if she had been unfaithful, it would have taken place in front of the children and household staff, and after warning her husband, knowing his jealousy. Yet this detail is ultimately secondary—the story’s outcome is evident from the start. The only remaining uncertainty concerns the fate of the violinist, which is not enough, in my opinion, to recommend the film to a wider audience. Unless you are a devoted admirer of literary classics or Tolstoy in particular, I would advise skipping it.

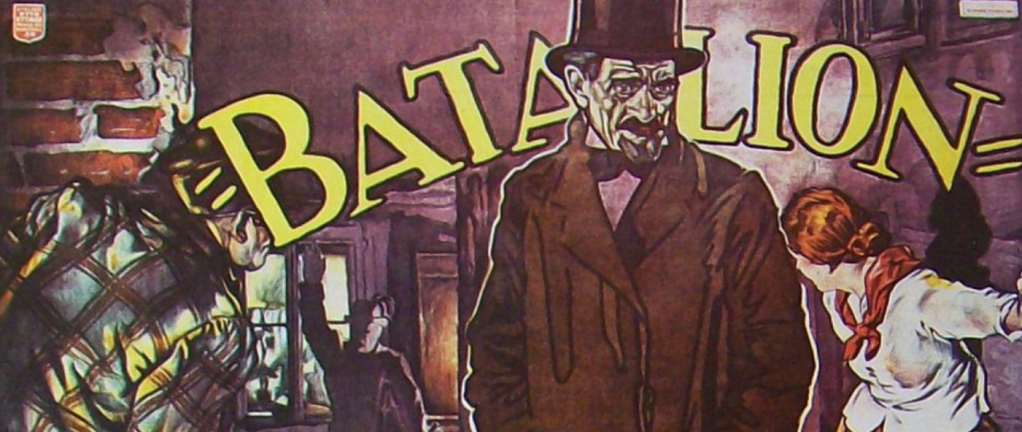

Krejcerova sonata (Крейцерова соната) – Vladimir Gardin (1914)

As an appendix, I should mention the only other surviving silent adaptation of Tolstoy’s novel. In addition to this version, there was a Russian film directed by Pyotr Chardynin (1911) and an American adaptation by Herbert Brenon (1915).

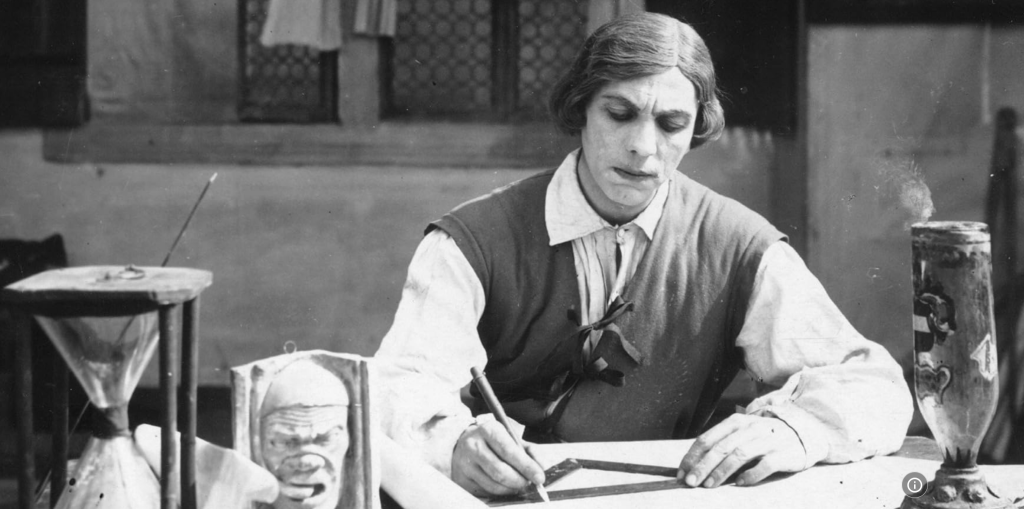

Gardin’s version is much shorter than Machatý’s and lacks the final portion of the story. Despite its brevity, it feels more introspective. With few intertitles, Pozdnyšev conveys his marital and relational struggles directly to the listening man—Tolstoy himself. Yet many elements that would deepen the narrative are missing, such as the motives behind the lovers’ encounters or the husband’s attempt at reconciliation. The cinematography is static (as expected in 1914) and not particularly striking. The actors are Boris Orskij as the husband and Elizaveta Uvarova as the wife. The narrative remains straightforward, offering little to attract a general audience. I watched and reviewed this film solely for the sake of completeness.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment