With Takový je život we stand at the very twilight of Czech silent cinema, a film that opens the door to the sound era in one of the most compelling ways imaginable. Loosely inspired by Émile Zola’s La curée, German director Carl Junghans sought to bring to the screen the story of an ordinary family but the path to production was anything but simple. As early as 1925 he attempted to have the film produced in Germany, only to face repeated obstacles that ultimately led him to Prague, where the project was finally realized. Can it therefore be considered a Czech film? Given the cast, the setting, and its place within Czech film history, I would argue that it absolutely can (at least within the scope of this project).

Through a series of everyday moments, the film follows the life of a working-class family: a woman (Vera Baranovskaja), tireless and selfless, always ready to help others; her husband (Theodor Pištěk), an alcoholic, unwilling to work and involved with another woman; and their daughter (Máňa Ženíšková), a beautiful young woman forced to take a job she despises simply to save a little money. Before long, their fragile balance collapses. All three lose their jobs, and the husband goes so far as to steal the family’s meager savings to buy alcohol, prompting his wife to throw him out of the house. In the final moments of the film, tragedy strikes in a cruelly ironic way. While washing clothes in boiling water, the woman tries to save a child who has dangerously leaned out of a window. She slips, falls against the basin, and is horribly burned. Her husband returns only at the very end, just in time to hold her hand as she dies. After the funeral, friends and relatives quietly head back home, resuming their lives.

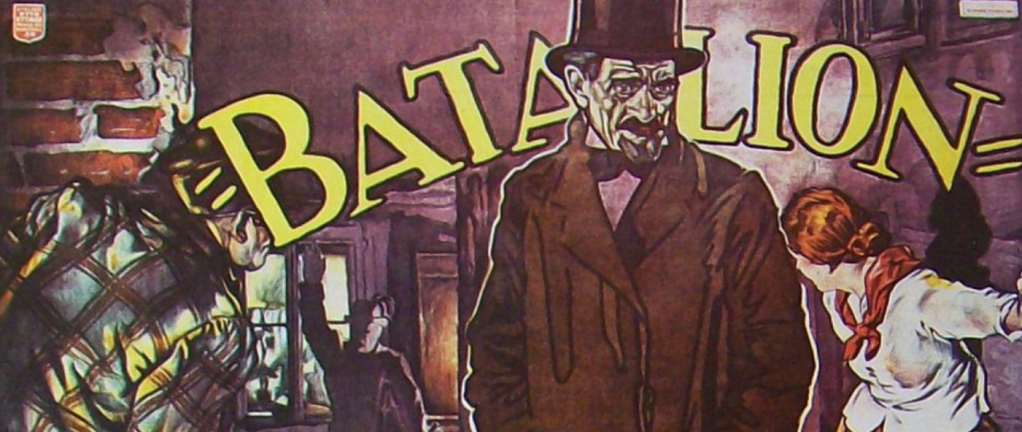

Here, the plot feels less like a narrative engine and more like a pretext to capture fragments of everyday life. Junghans brings us directly into the home during moments of labor and rest, observing a lower-class family that earns just enough to survive, sometimes not even that. The storyline gradually recedes into the background, while the camera focuses instead on countless small details of contemporary life, many of which I’ve tried to highlight through the images accompanying the original article. Junghans is particularly fascinated by hands: their movements, their gestures, the physicality of work. Each character is shown at least twice performing their job, as if to forge an inseparable bond between labor and daily routine. Perhaps for this reason, the film lacks a clearly defined historical setting, the events could have taken place at almost any moment in time. Another striking feature is the editing, which is extremely rapid and fragmented, often presenting the same scene through multiple shots and angles, as if offering the viewer several perspectives on the same reality.

The prevailing mood, however, is deeply pessimistic. Beneath the title—That’s Life—lies a profound sense of inevitability and suffering, something many of us have experienced and which seems to be an inescapable part of human existence. The film leaves the viewer with a lingering feeling of injustice. Vera Baranovskaja delivers a magnificent performance, creating a character who feels intensely alive: a woman who endures hardship with dignity, who rolls up her sleeves and keeps going without expecting help from above. That it is precisely she who is punished, rather than the idle, morally corrupt husband, subverts the familiar moral logic of American or Scandinavian cinema of the period and leaves the viewer unsettled. There is no justification for her tragic fate, no moral lesson to soften the blow. And perhaps that is the film’s most devastating truth: life, quite simply, can be like this.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment