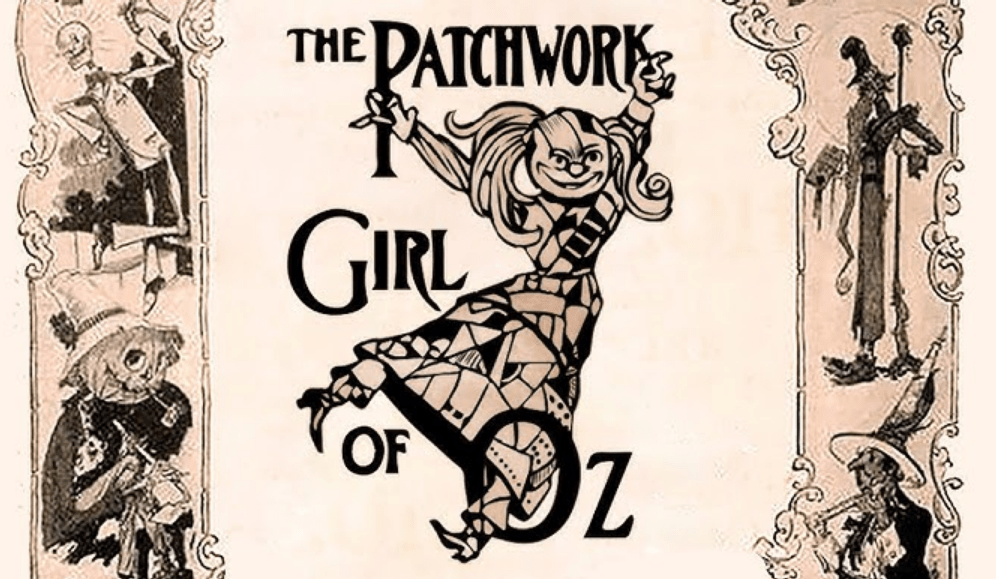

Ten years after the publication of the first book in the Oz series, what L. Frank Baum intended to be its final installment was released: The Emerald City of Oz (1910). At the end of the novel, Oz becomes inaccessible to anyone from the outside world, effectively severing its connection with reality. Needless to say, Baum was soon overwhelmed by letters from disappointed fans, which persuaded him to “attempt communication with the Land of Oz by means of a wireless telegraph.” The experiment must have worked, because in 1913 The Patchwork Girl of Oz was published. Around the same time, Baum had founded his own production company, The Oz Film Manufacturing Company, and in 1914 he released a film adaptation aimed both at promoting the book and capitalizing on its success in order to recover production costs.

Little Ojo (Violet MacMillan) lives in a remote forest with his guardian, Unc Nunkie (Frank Moore). Tired of their life of hardship, the two set out for the home of Dr. Pipt, better known as the Crooked Magician (Raymond Russell), who lives there with his wife Margolotte (Vera Dranet) and their daughter Ojo’s cousin, Jinjur, renamed in the film as Jasseva (Bobbie Gould). The magician is in the process of creating a life-giving powder to animate a Patchwork Girl, Scraps (Pierre Couderc). Since Scraps is meant to serve as a maid, her creator deliberately leaves her without a brain, but Ojo secretly decides she might need one and gives her his own. When the Patchwork Girl comes to life, something goes wrong: startled, Dr. Pipt accidentally petrifies Margolotte, Unc Nunkie, and Danx (Richard Rosson), Jasseva’s fiancé. To reverse the spell, the group must obtain three rare ingredients: hairs from the tail of the Woozy, some six-leaved clover, and water from the Dark Well. Dr. Pipt leaves in search of the water, while Ojo, Scraps, and Jasseva, who brings along her fiancé in miniature form, set out to find the remaining ingredients. They first encounter the Woozy (Fred Woodward), whom they are forced to take with them because they cannot pull any hairs from its tail. Later, while attempting to collect the forbidden clover, they are arrested. Only Scraps manages to escape and eventually reunite with the Crooked Magician. After numerous dangers and encounters with bizarre peoples—the Tottenhots, the Horners, and others—the group finally obtains the Dark Well water. On the day of judgment, before a tribunal that includes Dorothy, the Cowardly Lion (Hal Roach), the Scarecrow (Bert Glennon), and the Tin Woodman (Lon Musgrave), the protagonists are acquitted by Queen Ozma (Jessie May Walsh), who allows the Crooked Magician to perform the spell that restores their petrified friends to life.

I have described the plot in detail because, as anyone familiar with the novel will immediately notice, the film differs significantly from Baum’s original story—often without clear narrative justification. This is particularly striking given that Baum himself wrote the screenplay, and many elements could easily have been translated directly to the screen. Among the most notable changes are:

- The introduction of Jasseva and Danx, along with a new subplot involving Jinjur, who repeatedly steals Danx’s miniature statue after falling in love with it.

- The Glass Cat, difficult to realize onscreen, is largely replaced by a mischievous and unidentified equine creature (once again).

- The Crooked Magician himself joins the quest (traveling to the Dark Well), while the second group is expanded to include Jasseva and, at least initially, a number of troublesome Munchkins.

- The group is arrested by city guards and imprisoned in a conventional jail, rather than the reformatory prison featured in the book.

- The Tottenhots and the Horners are no longer at war; instead, the Tottenhots threaten to cut off the leg of anyone who has “one too many.”

- Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Woodman no longer actively assist the protagonists during their journey.

- The ending omits both Ozma’s sudden deus ex machina resolution and the Crooked Magician’s loss of his powers.

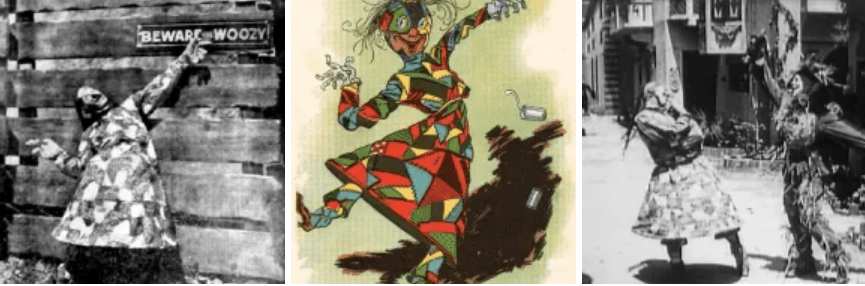

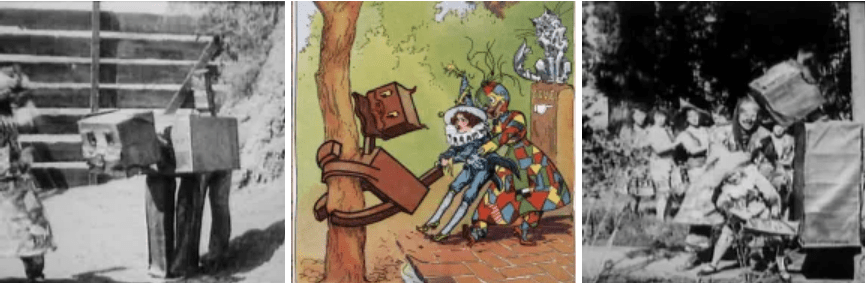

Turning to the film itself, The Patchwork Girl of Oz is certainly superior to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Otis Turner, 1910), but it still presents several issues for modern viewers. Scraps is portrayed as excessively hyperactive, never remaining still for even a single frame. While the character is indeed curious and exuberant in the book, the film pushes this trait to an almost exhausting extreme. More generally, perhaps in an effort to emphasize spectacle and entertainment, the film relies too heavily on dances and broadly “comic” interludes. The most charming moments are arguably those employing paired movement, such as the scene in which Scraps is magically assembled. From an iconographic standpoint, however, the film is particularly interesting. Being produced under Baum’s direct supervision, it maintains strong continuity with John R. Neill’s original illustrations. Especially delightful is the depiction of the Woozy, rendered as a boxy, oversized feline creature remarkably faithful to its appearance in the book.

In conclusion, The Patchwork Girl of Oz offers a fascinating example of how an author with full control over his creation can shape its visual identity across different media, from literature to cinema. At the same time, it also demonstrates that such creative freedom does not necessarily guarantee a successful result. The film remains difficult to appreciate today, and given the short-lived failure of the Oz Film Manufacturing Company, it appears it did not fully win over audiences even at the time of its release.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment