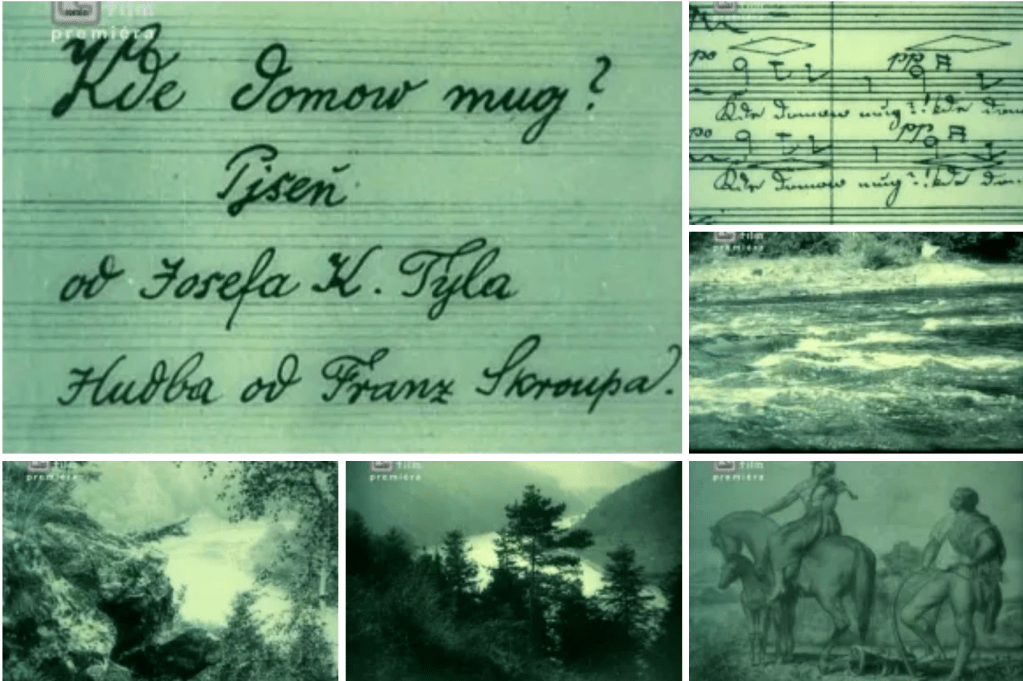

As we’ve seen more than once, early Czech cinema often turned to cultural figures who had kept the national spirit alive under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Josef Kajetán Tyl was one of them: writer, actor, and playwright, he is perhaps best remembered as the author of the 1834 verses that became the Czech national anthem, Kde domov můj (“Where My Home Is”), set to music by František Škroup as part of the operetta Fidlovačka aneb žádný hněv a žádná rvačka (“Fidlovačka, or No Anger and No Brawling”).

Where my home is, where my home is,

Water roars across the meadows,

Pinewoods rustle among rocks,

The orchard is glorious with spring blossom,

Paradise on earth it is to see.

And this is that beautiful land,

The Czech land, my home,

The Czech land, my home!

Where my home is, where my home is,

If, in the heavenly land, you have met

Slender souls in spry bodies,

Of clear mind, vigorous and prospering,

And with a strength that frustrates all defiance,

That is the glorious nation of Czechs

Among the Czechs (is) my home!

Among the Czechs, my home!

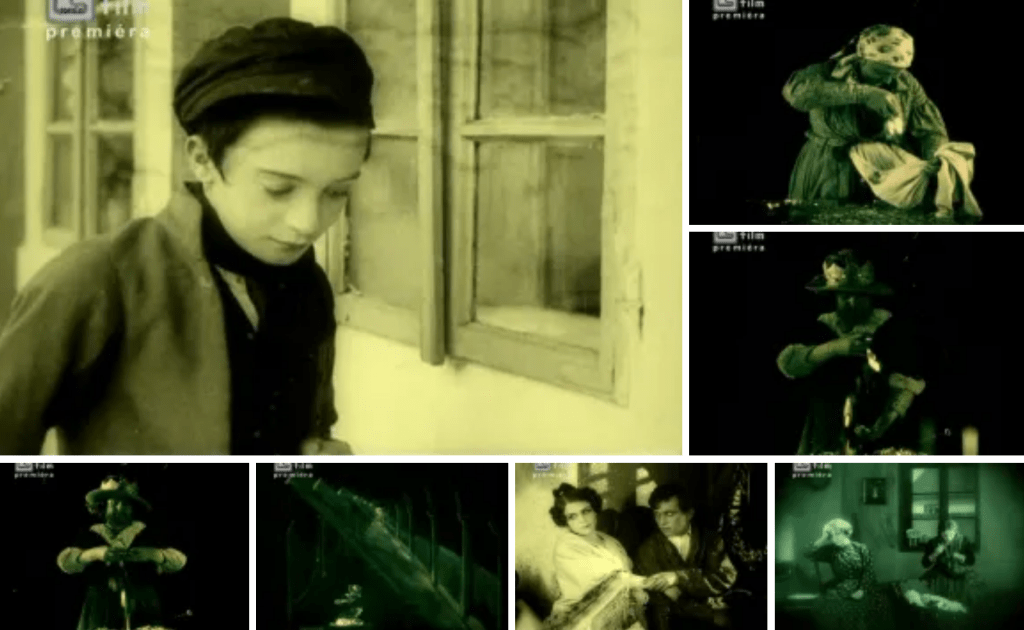

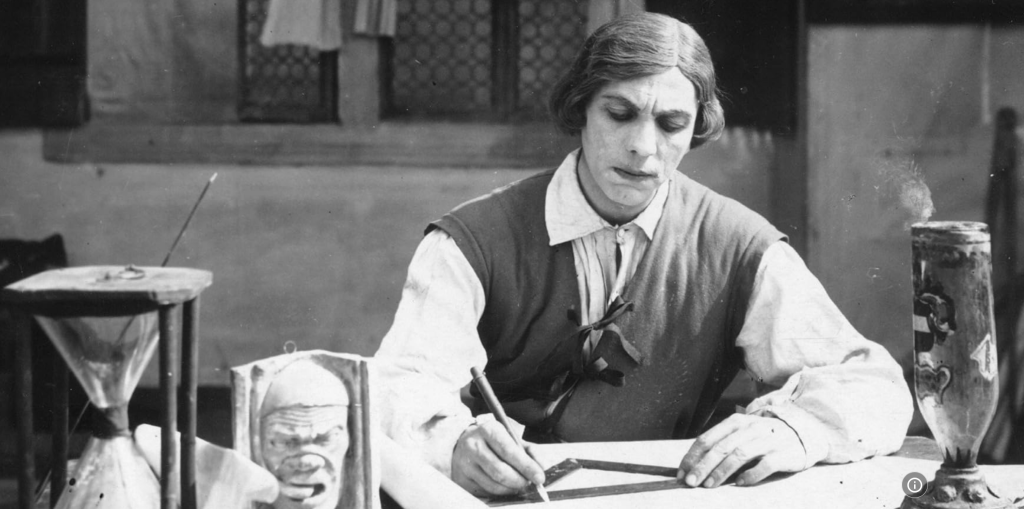

Tyl’s life (Zdeněk Štěpánek), dramatized by director Svatopluk Innemann in this two-hour biopic, was far from simple. Born into poverty, his musical and literary talents earned him a place in Prague, where he joined a theater troupe that included his future wife Magdalena Forchheimová (Helena Friedlová). Soon he was staging plays at the Stavovské divadlo (Prague’s Estates Theatre), including Fidlovačka. There he also met his second partner, Anna Forchheimová-Rajská (Zdena Kavková), Magdalena’s sister — living with both women without ever divorcing the first. The film follows his growing political engagement after the revolutions of 1848, inspired in part by the writer Karel Havlíček Borovský (Jan W. Speerger). Tyl takes part in an attempted uprising, is wounded, and sees the rebellion crushed in blood (historically in March 1849). His revolutionary sympathies lead to exile, and he is forced to leave with his family. From there, his fortunes collapse. He dies in poverty before reaching the age of fifty.

Formally, the film feels strikingly modern for 1926. Drawing on a study by Josef Ladislav Turnovský (whose accuracy I can’t assess), it strives for realism in its sets, costumes, and staging. Without subtitles, some nuances are inevitably lost, but the story remains easy to follow for anyone familiar with Czech history. The production values are impressive: the sheer number of characters, elaborate sets, and detailed costumes suggest a local “colossal,” with a correspondingly high budget.

Two moments stood out in particular: the young Tyl setting off from home, dreaming of wealth that might feed his family, and the poetic sequence of the anthem’s creation, where Innemann cuts to landscapes and painterly images evoking the Czech homeland.

As a film, Josef Kajetán Tyl is compelling. The subject’s life offers rich material, and those fond of “romantic, doomed poet” narratives will likely find it appealing. At the same time, the very specificity of his story, combined with the lack of translated intertitles and the film’s length, may pose significant barriers for viewers less versed in Czech history.

This article was originally published in Italian on emutofu.com

Leave a comment